|

You may have noticed that many people have trouble deciding what to call those who went through the ordeal called Katrina. They have been called victims, evacuees, survivors, refugees, or displaced citizens. What you call them is a litmus test given by those who police your speech and thought on the subject.

If you are fortunate enough to spend time actually talking with a Katrina [your word here], you immediately realize that any of these terms is inadequate. The simple truth is that Katrina is something that happened to them; it is not who they are. The people trapped in New Orleans had lives before Katrina turned them upside down. They had homes, jobs, families, and friends. They had lives in New Orleans, and it is those lives that define them, not Katrina.

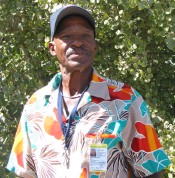

Mack Murphy was born in Louisiana and lived in New Orleans from 1949 until 2005. He had a house and worked a variety of jobs. He loaded tucks for the Pepsi Cola Company. He worked on River helicopters as a helper. He did construction work for his brother, Lawrence. He gained experience doing demolition and carpentry at his brother’s company, and as he told me, he has experience, but no title.

Mack Murphy

Most of his family lived in New Orleans, so the city was more than a place. It meant family ties.

On Sunday, Aug. 28, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin issued the first ever evacuation order for the city. So Mack followed the instructions for evacuation he heard on the news. Mack left his house on his bicycle and tried to make his way to the Superdome. He made it as far as the bridge on Clayborne St. and Tulane. He rode to his sister’s house in the 12th Ward, finding water coming up to the floor.

Eventually, he made his way to the Superdome, where he met his brother-in-law and "some guys." He was there for four days, until Aug. 31.

When asked about his experiences and actions during that time, Mack repeatedly responded "That’s a hard decision."

While he was at the SuperDome, he saw a woman in a wheelchair die in front of him. It was the first time he had ever seen a person die.

That wasn’t the worst thing that he had to go through. For Mack, being separated from his family and being unable to communicate with them was the hardest part. His brother, Lawrence had been hospitalized before the storm hit. He didn’t know what happened to him, and he had no way to reach him. Mack found out later that he had been at the Morial Convention Center. He learned this after he left New Orleans.

Mack’s memories of his evacuation are sketchy. He says he was evacuated from the Convention Center and placed on an airplane on one of the interstate highways. It was his first time on a plane. He was taken to Louis Armstrong International Airport and put on another plane and sent to Houston. He doesn’t know who was in charge, he simply followed instructions. When he was put on the plane he asked where he was going. He didn’t find out he was going to Denver until he was on the plane.

When I asked him how he felt about coming to Denver, he leaned back, paused, and said, "That’s a hard decision."

The evacuation process added to the strain greatly. Coming to Denver meant he was free, no longer trapped in New Orleans. It also meant further separation from his family because they were all sent to different places. His brother is in San Antonio, his sister is in Houston, despite having kin in Atlanta.

When asked what he needed now, he named the basics, the things that everyone needs: a house, and a job. When asked if he would return to New Orleans, he said, "Just to look around to see what it was like, not to live."

Looking back over his experience, Mack says now that Katrina was unexpected despite having lived in New Orleans since 1949. He had previous experiences with hurricanes. He remembered when Hurricane Betsy hit in 1965 that the Ninth Ward was flooded. He remembered having to get on top of a school’s roof during that storm. He remembered Hurricane Camille in ‘68. He remembered Flossy in the 1950s.

He said that when something like this happens, "All you do is just pray and ask the Lord, you know?"

But Katrina still came as a total surprise to him.

Dana Bell considered herself part of the African American middle-class. She was born in New Orleans and had lived and worked there most of her life. She managed the sterilization department at Memorial Medical Center. Her mother, Gloria, had been a nursing assistant at LaFon Homes, a nursing home. Her grandmother, Mrs. Mary Johnson, was a registered nurse and director of the same nursing home. So when the evacuation order was given for the city, Bell left her home in Mid City, got in her brand new car, filled up the tank, and went to the house her grandmother had lived in for 65 years to get the two women, both of whom were in wheelchairs.

Dana Bell

They refused to go. So, Dana stayed with them. After all, she said, "I was dealing with two mothers." And, after all, city officials had cried wolf before every hurricane.

That is how she found herself in her 93 year-old grandmother’s home when the worst of the flooding hit. It began at 9 a.m. on Monday. By 4 p.m. the water was chest high inside the house. Dana had to physically lift and carry two wheelchair bound women onto beds so they wouldn’t drown. She saw a boat outside, raised a window, and shouted out for help. The Department of Wildlife and Fisheries had sent people to evacuate elderly residents in the neighborhood. They told Dana and other neighbors that they would have to come back for them. They waited from 4 p.m. to 12 a.m.

Dana heard her neighbors shouting for her to come out, telling her to open the door. She was afraid that if she did that more water would flood the house. What she didn’t know was that the house was level with the floodwaters, so she was able to open the door and step out onto the porch. Helicopters could be heard overhead, and she had a flashlight, something most of her neighbors didn’t have. She found herself using it to flash SOS, trying to get their attention.

By this time, the water had covered most of the furniture in the house the only dry spot she could find was on a bed in another room, away from her mother and grandmother.

At 12 a.m., two boats finally came. The three of them were evacuated to an interstate, where they remained until 12 p.m. the next day. An ambulance came and the three women were relocated to the Superdome, where they waited for another 48 hours. It was a disorienting experience, and Dana began to lose track of time.

She had a cell phone, but it was out of power. Someone had a charger, so she stood in line for two hours waiting to use it. Once she got there, the jack on her phone broke.

This was when everything began to hit her. She had two women she loved looking to her to take care of things, and when the phone broke, she felt as if she had failed them.

|

|

She went outside, and almost cried. She felt a tap on her shoulder, turned and saw a little girl who said to her, "My auntie wants you." The little girl’s aunt was someone she used to work with, and she knew what it meant when Dana walked away from something. This was fortunate, because Dana just couldn’t face her mother and grandmother until her friend talked her down.

Meetings like this happened again, luckily. Dana, Gloria, and Mrs. Johnson were finally evacuated, placed on an Army dump truck and taken to another interstate, with tens of thousands of others outside in the hot sun, eating army rations, waiting. While she waited, she met another friend who had a working cell phone, and she was finally able to call her sister who lived in Washington, D.C. to let the family know they were fine.

Dana was told that they had to move again to a Special Needs area because her mother and grandmother were in need of medical attention. In order to do this, Dana had to push two wheelchairs by herself. Luckily, she saw a friend’s 19 year-old daughter and seven year-old son. They had been separated from their mother, so they joined together to help one another. The young woman would help with one of the wheelchairs and Dana would look after them.

Once they were in the Special Needs area, they waited there from 12 a.m. until 6 a.m. They saw people die and saw body bags filled with the dead. Finally, a chartered bus arrived to take people away. When the five of them tried to board, Dana was told that the little boy would have to stay. Only one helper per special needs person would be allowed.

Dana refused to leave him behind. She said that he was going even if he had to sit on her lap, but he was getting on that bus.

Once they were on the bus, they were accidentally taken to Louis Armstrong International Airport. The bus driver, for some reason, took them there. Once they arrived, no one knew why they were there or what to do for them.

It was a lucky thing. Delta Airlines happened to fly in with emergency rations and a representative saw all these people stranded there. The airline offered to fly 90 of the evacuees to Atlanta free of charge and from there to any destination, free of charge. Needless to say, they took the offer.

Dana wanted to go to Washington, D.C. where her sister lived. So, how did the three of them find themselves in Denver? Family. One brother lived in Longmont, another in Thornton. For the five days the three women were stranded and moved about, their family was sure that they had drowned. The family got together and decided that they should go to Colorado instead. It was a series of lucky accidents rather than the procedures of officials in charge that allowed the family to remain intact and to be reunited, unlike many others who have been separated and dispersed across the country.

This experience was a wake up call for Dana. As she said, she had been employed for all of her adult life. "I didn’t have much, but what I had, I earned." Even so, she had no idea of the extent of the poverty that existed in New Orleans. Dana and her family had been part of the Black middle-class for generations. She knew that poor people existed but her time at the Superdome revealed to her what it meant to be a have-not.

Marshall Jackson is one of those men everyone in a Black community knows. Hard working. Constantly busy, always moving, always doing something. Black men like this are rarely seen in mainstream media, but we know them well. Marshall is a retired fireman (as he prefers to be called). He is "New Orleans, born and raised." He’s a Navy veteran who served from 1961 to 1968. He joined the Fire Department in 1973 and retired in 1993. He worked for a shuttle company, driving passengers to and from downtown. He has been married to his wife Sheila for almost six years. Sheila is Dana Bell’s sister, which makes Marshall an in-law to Dana, Gloria, and Mrs. Johnson as well.

Marshall Jackson

Marshall and Sheila lived in their apartment in Eastern New Orleans when Katrina hit. Marshall’s background provides an interesting perspective. He had been home on leave when Hurricane Betsy hit in ’65. He had just been released from the Navy when Camille came through. By the time he retired he was a trained professional who knew what to do in emergencies. He had seen storms and flooding before. He knew what needed to be done – stock up on water and food, and be patient until it passes.

Katrina came and went, and everything was quiet. It was as dry in New Orleans that next morning as it was the day I interviewed him at Lowry.

Then the waters started rising, and he knew. This was something he had never seen before. The natural question to ask is why hadn’t he evacuated when the order came? The answer was one I had heard before. The city had cried wolf before, and he thought things would be alright.

He and his wife spent four days in their apartment waiting for help. They lived on the second floor, and the water was 12 feet deep. While they waited, they worried about their family. Sheila had no idea what her mother, sister, and grandmother were going through. Marshall was worried about his 90 year-old father, Jesse, who also lived in the city. When they were finally airlifted out by the Coast Guard four days later, Marshall learned that his uncle had picked up his father before the storm hit and he was safe in Houma, La.

Marshall and Sheila were taken to Houston, then came to Denver, where their family was reuniting. For him, the hardest part was exactly what others have said: Not knowing about his family who lived in New Orleans and who were such a central part of his life.

Now, three weeks later he finds himself in Colorado with his in-laws. He watches the news to keep up on what is happening in New Orleans, and it has contributed to his decision to remain in the Denver metro area. When he hears the reports, he knows that the city won’t be safe. He knows that there will be health concerns and that the city won’t be cleaned up enough. He sees those with means will be a safe, but that others will be left out.

When asked what affect Katrina has had on him, he answers that it was big. He had been through Betsy and had to go out in that storm to evacuate his mother. He was able to drive through that. But Katrina was the worst.

I overheard someone say that Marshall still dreams about New Orleans. He said that was true, that he had trouble sleeping at first, and when he does sleep, he does dream. But, he added, he was getting past it and things would get back to normal.

In fact, he finds himself getting antsy. He told me that he needs something to do. He needs to work.

Sounds normal.

Two other Katrina evacuees, Clay Lewis and a student from New Orleans, regroup after being moved to Denver.

|